Yule: Viking Origins Explained- When is Yule and its Traditions?

Share

Yule

Welcome! With a plethora of bad information on the internet, it has long frustrated Scandinavians, Academics and followers of the Old Norse religion when there has been so much misinformation on Yule. The first and most common piece of misinformation comes from the well known Wicca Wheel of the Year which puts Yule on the COMPLETELY INCORRECT day of the Winter Solstice.

On our Norse calendar that we sell on our site that you can find at this link(2025 calendar), it lists Yule on the correct date and includes a few of the celebrations and traditions that are most commonly found in the viking age sources. This article is to go along with our calendar and to examine all of the archeology, written sources, and linguistic evidence from the viking age and beyond, to show people the real origins of Yule!

Our Historical Norse Calendar. Read the full blog here.

Chapters & Content if you want to skip ahead:

-Linguistic Evidence

-Medieval Sources

-The Gothic Calendar

-Norse Sources

-The Origins of Yule

-When Is Yule Celebrated?

-Yule Annual or Every 9 Years?

-Oaths, Toasts, and Boasts

-The Sónargǫltr: The Sacred Yule Boar

-Gift Giving and Merry Making

-The Post-Yule Depression

-Supernatural Events

-No Violence for 3 Days

-Drinking at Yule

-Yule Conclusion

Linguistic Evidence of Pagan Yule Traditions

To begin, let us examine the etymology of Yule, a word that highlights its significance as a festival deeply rooted in Germanic tradition. While many Norse sources from the Viking Age reference Jul as part of their pagan traditions, it is important to note that the celebration of Yule was not uniquely Norse. By examining parallel terms in related languages, it becomes evident that Yule was likely a widespread holiday among all Germanic peoples.

The earliest written records of the word appear in Old English, dating as far back as the 7th century. The modern English term "Yule" derives from Old English ġēol, with earlier forms such as geoh(h)ol, geh(h)ol, and geóla. In Old English, ġēol or ġēohol referred to the 12-day midwinter festival of "Yule," while ġēola or ġēoli denoted the months surrounding it. Specifically, ǣrra ġēola referred to December (the period before the Yule festival), and æftera ġēola referred to January (the period following Yule).

Even older records of the term appear in Gothic as 𐌾𐌹𐌿𐌻𐌴𐌹𐍃 (jiuleis). The Goths, a Germanic people who migrated and established a kingdom in Eastern Europe, preserved the term in their calendar from the 5th–6th century CE recorded in the Codex Ambrosianus A. The month fruma jiuleis ("first Yule") suggests that the holy time of midwinter was already celebrated at least 1,500 years ago.

All these terms are believed to derive from the Proto-Germanic word jehwlą, meaning "festivity" or "celebration." The Proto-Germanic language, dating back much more than 2,000 years, suggests that Yule could be an even older tradition. While there are possible Indo-European parallels for the term, these connections remain debated and will not be explored further here.

Thus, while Jul is well-documented in Norse sources, it is clear that the midwinter celebration was a shared cultural event among Germanic peoples. The Norse tradition simply preserved the most detailed accounts. With that understanding, let us now turn to the specific written sources on Yule.

Medieval Sources on the Pagan Holiday Yule

One of the earliest written references to Yule comes from the 8th-century English historian Bede. In his work, De Temporum Ratione (The Reckoning of Time), Bede describes the Anglo-Saxon calendar and its inclusion of the months geola or giuli. These months correspond to either modern December or the period spanning December and January.

Se mōnaþ is nemned on Leden Decembris, and on ūre geþeōde se ǣrra geōla, forðan ða mōnþas twegen syndon nemde ānum naman, ōðer se ǣrra geōla, óðer se æftera.

The month is called in Latin December, and in our language geōla for two months enjoy the same name; the first one Se Ǣrra Geola [The Preceding Yule] and the other Se Æftera [The Following].

-Bede, De temporum ratione, 725ce

Bede's account highlights the significance of midwinter in the Anglo-Saxon year, offering valuable evidence that Yule was an established and meaningful time of festivity well before the Christianization of England. His record serves as an important link between the Norse and Anglo-Saxon traditions, illustrating how geola marked a pivotal point in the Germanic cultural calendar.

The Gothic Calendar: Evidence from the 5th Century

Even older than Bede’s Anglo-Saxon account is the Gothic calendar preserved in the Codex Ambrosianus A, which dates to the 5th century CE. This calendar includes the month name fruma jiuleis ("first Yule"), providing concrete evidence that Yule was celebrated among the Goths, a Germanic people who established their kingdom in Eastern Europe.

This reference not only predates the Anglo-Saxon records but also solidifies the idea that juleis was a recognized midwinter period across Germanic cultures. The Gothic calendar serves as a valuable testament to the shared heritage of Yule traditions within the broader Germanic world, demonstrating their continuity and significance over centuries.

Norse Sources on Celebrating Yule and Its Rituals

The Old Norse word for Yule was jól, closely resembling the modern Scandinavian terms: Swedish, Danish, and Norwegian jul, as well as the Icelandic and Faroese jól. The word jól appears frequently in Norse texts and carries rich associations with midwinter celebrations and the gods themselves.

In Skáldskaparmál (chapter 55) from the Prose Edda, jól is intricately connected to divine beings. One of the poetic names for the gods is "Yule-beings" (jólnar). The skald Eyvindr skáldaspillir is quoted in this text, using the term in a verse:

"again we have produced Yule-being's feast [mead of poetry], our rulers' eulogy, like a bridge of masonry."

This verse ties Yule not only to the gods but also to the tradition of poetic and celebratory feasts, emphasizing its cultural and spiritual importance.

Additionally, one of Odin's many names is Jólnir, directly referencing jól and reinforcing its association with him and the gods. In Ágrip af Nóregskonungasögum, a 12th-century text, jól is explicitly interpreted as deriving from Odin’s name Jólnir, linking the term closely to Norse mythology and its pantheon.

These references in Norse literature highlight the sacred and multifaceted nature of Yule, demonstrating its deep roots in Viking Age spirituality and culture.

From this point onward, we will use the modern English term "Yule" for clarity and consistency. However, it is important to remember the Norse and broader Germanic origins of this word, deeply rooted in the cultural and spiritual traditions of these ancient peoples. The term carries with it a legacy of midwinter celebrations, divine associations, and poetic significance that have influenced its modern usage.

The Origins of Yule: Understanding the Days of Yule

One of the earliest references to Yule can be found in Ynglinga Saga, often considered the oldest source on the topic. According to this saga, when Odin migrated to Scandinavia from Asaland (a mythical homeland, roughly dated in the text to the time of Jesus), he established the laws for when the three major blóts (sacrifices) should be held. While the saga does not explicitly use the term "Yule," it does reference "midwinter," a term confirmed by other sources to refer to Yule.

"Odin established the same law in his land that had been in force in Asaland. {....}. On winter day there should be blood-sacrifice for a good year, and in the middle of winter for a good crop; and the third sacrifice should be on summer day, for victory in battle."

-Ynglinga Saga, ch.8

The text specifies that during midwinter, a sacrifice should be made for a good crop. This suggests that the midwinter sacrifice was likely dedicated to Freyr, the god of fertility and harvests, an association that is supported by other sources, which will be discussed shortly. Ynglinga Saga thus ties the origins of Yule to Odin's establishment of sacred traditions in Scandinavia, marking it as a time for both ritual and agricultural blessings.

Another fascinating story from Ynglinga Saga highlights the inclusion of children and games during midwinter festivities, providing insights into the social and ritual aspects of Yule. In this account, two young princes, around six years old, were playing what appears to be a battle strategy game. This suggests that children were not only present but actively engaged in activities at the original Yule celebrations. Games were clearly a part of the festivities, emphasizing both communal bonding and the development of skills valued in Norse society.

The story also takes an intriguing turn when one of the boys, who was shamed for not being as strong as the other, was fed a wolf’s heart. From that day forward, he became ferocious and extraordinarily strong for the rest of his life. This element hints at a possible connection to berserker (berserkir) or ulfhedinn (wolf-warrior) initiation rituals, which may have taken place during Yule. The symbolic act of consuming a wolf’s heart to gain its strength ties in with known Norse practices of using sympathetic magic to invoke specific traits.

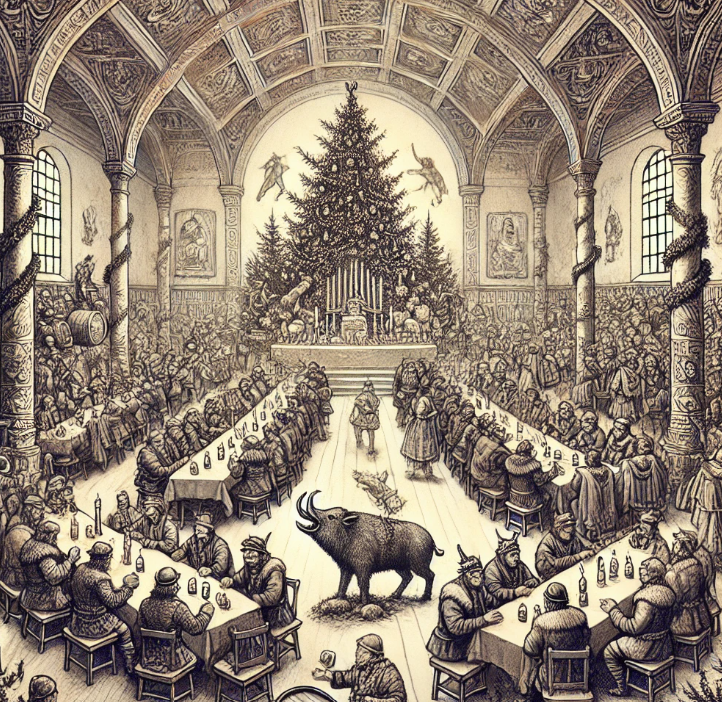

"There also were held the mid-winter sacrifices, at which many kings attended. One year at midwinter there was a great assembly of people at Upsal, and King Yngvar had also come there with his sons. Alf, King Yngvar's son, and Ingjald, King Onund's son, were there -- both about six years old. They amused themselves with child's play, in which each should be leading on his army. In their play Ingjald found himself not so strong as Alf, and was so vexed that he almost cried. His foster-brother Gautvid came up, led him to his foster-father Svipdag the Blind, and told him how ill it appeared that he was weaker and less manly than Alf, King Yngvar's son. Svipdag replied that it was a great shame. The day after Svipdag took the heart of a wolf, roasted it on the tongs, and gave it to the king's son Ingjald to eat, and from that time he became a most ferocious person, and of

the worst disposition."

-Ynglinga Saga ch.38

Of course, a feast was also part of the celebration, as confirmed by nearly all sources on Yule. Feasting, games, and possible initiation rites together paint a vivid picture of Yule as a multifaceted festival encompassing social, ritual, and spiritual dimensions.

When Is Yule? Yuletide Winter Solstice?

One of the most critical sources on Yule tells us about its timing. In an effort to convert the pagans, King Haakon moved the Yule celebration from its traditional midwinter date to align with the birth of Jesus, which Christians celebrated at that time. It’s important to note, however, that in the Middle Ages, Christians often observed the birth of Jesus on the Winter Solstice rather than on December 25th as we do today. Exact dates from this period are not always provided, so there is some uncertainty.

"King Hakon was a good Christian when he came to Norway; but as the whole country was heathen, with much heathenish sacrifice, and as many great people, as well as the favour of the common people, were to be conciliated, he resolved to practice his Christianity in private. But he kept Sundays, and the Friday fasts, and some token of the greatest holy-days. He made a law that the festival of Yule should begin at the same time as Christian people held it, and that every man, under penalty, should brew a meal of malt into ale, and therewith keep the Yule holy as long as it lasted. Before him, the beginning of Yule, or the slaughter night, was the night of mid-winter (Full moon in Jan.), and Yule was kept for three days thereafter."

-Saga of Hákon góði ch. 15

Today, one of the leading scholars on pagan calendars, Andreas Nordberg, dates Yule to the first full moon after the new moon following the Winter Solstice. His interpretation is supported by evidence from the primstav (traditional Norwegian calendar stick), which also aligns with this timeline.

Primstaven(earliest ones dated to the 12th century)

According to this calculation, Yule would fall in mid-January, approximately three months(moons) after the start of winter (Vetrnætr), which is commonly referred to as midwinter.

The celebration itself spanned three days, with the first day—almost certainly marked by the full moon—being the central day of Yule. The sacrifice occurred on this day, followed by two additional days of feasting and celebration, creating a three-day festival to honor the gods and the season.

Another mention of Yule appears in Haakon’s Saga, providing a fascinating glimpse into the customs surrounding the festival. On the first day of Yule—remember, Yule was a three-day celebration—a Jarl’s son was born. He underwent "vatni ausinn", the pagan baptism ritual, which was likely not much different from the Christian baptism. During this ceremony, he was given his name, and that baby grew up to be the legendary Jarl Haakon, renowned as one of the greatest warriors and chieftains in the history of northern Europe.

"King Hakon kept Yule at Throndhjem, and Earl Sigurd had made a feast for him at Hlader. The night of the first day of Yule the earl's wife, Bergljot, was brought to bed of a boy-child, which afterwards King Hakon poured water over, and gave him his own name. The boy grew up, and became in his day a mighty and able man, and was earl after his father, who was King Hakon's dearest friend."

-Saga of Hákon góði ch.12

This story highlights a recurring theme: children born during Yule, whether on the first full moon after the Winter Solstice (the original pagan date) or on the Solstice itself (after King Haakon’s changes), often became extraordinary figures. It is worth noting that being born during Yule suggests conception during the spring, around the time of the pagan festival Austr (modern Easter), further tying fertility and rebirth themes into the cycle of the seasons.

Yule Annual or Every 9 Years? Exploring the Rituals for Yule

Thietmar of Merseburg provides one of the most valuable first-hand accounts of Yule, describing the sacred midwinter sacrifices held in Lejre, Denmark. According to his record, these sacrifices were conducted every nine years, which differs from other sources that indicate Yule was an annual event. However, Thietmar’s account is especially significant because he directly places the celebration in January, aligning with other evidence that ties Yule to the first full moon after the Winter Solstice.

"Because I have heard strange stories about their ancient sacrifices, I will not allow the practice to go unmentioned. In those parts the center of the kingdom is called Lederun (Lejre), in the region of Selon (Sjælland), all the people gathered every nine years in January, that is after we have celebrated the birth of the Lord [Jan 6th], and there they offered to the gods ninety-nine men and just as many horses, along with dogs and cocks— the later being used in place of hawks."

-The Chronicon of Thietmar of Merseburg, 10th century

Unlike sagas written centuries after the events they describe, Thietmar’s writings are contemporary and therefore considered the most reliable source we have on this aspect of Yule. His observations give us a rare glimpse into the sacred rites of the Viking Age, underscoring the importance of midwinter in the Norse pagan calendar.

Oaths, Toasts, and Boasts: Sacred Yule Traditions

One of the key sources for Yule traditions is Hervarar Saga ok Heiðreks (The Saga of Hervör and Heidrek), which provides two detailed accounts of Yule celebrations. In one account, the saga describes how oaths were taken and boasts were made, a practice referred to as heitstrenging. This tradition bears striking similarities to the Sumbl or Symbel ritual found in the Old English text Beowulf, which dates back hundreds of years before the Viking Age.

The heitstrenging and Symbel rituals involve making toasts, swearing oaths, and boasting about one’s deeds or the accomplishments of one’s ancestors. This continuity between Norse and Anglo-Saxon traditions strongly suggests that this practice was one of the oldest and most enduring elements of Yule. These rituals, central to both community bonding and individual honor, highlight Yule’s deep cultural significance as a time for celebration, reflection, and the reinforcement of social and familial ties.

"It was Yule Eve, the time for men to make solemn vows at the ceremony of the bragarfull, or chief’s cup, as is the custom. Then Arngrim’s sons made vows. Hjorvard took this oath, that he would have the daughter of Ingjald king of the Swedes, the girl who was famed through all lands for beauty and skill, or else he would have no other woman."

-Hervarar saga ok Heiðreks ch. 3

The Sónargǫltr: The Sacred Yule Boar and Its Role in Yule Rituals

Another fascinating example from Hervarar Saga ok Heiðreks describes the sónargǫltr, the sacred sacrificial boar. Before the boar was sacrificed during Yule, each man would place his hand on the boar’s head and bristles and swear an oath. This ritual highlights the deep connection between Yule and the communal act of swearing oaths, reinforcing bonds of honor and commitment.

"King Heidrek settles down now and becomes a great chieftain and a wise sage. King Heidrek had a great boar reared. It was as big as the biggest of the full grown bulls and so fair that every hair on it seemed to be of gold. The king lays his hand on the head of the boar and his other hand on its bristles and swears this: that there is no one, however much wrong they may have done him, who won’t get a fair trial from his twelve wise men, and those twelve must look after the boar. Or else the accused must come up with riddles which the king could not guess. And King Heidrek now gets to be very popular."

-Hervarar saga ok Heiðreks ch. 10

This practice is almost certainly the origin of the Christmas ham that many of us enjoy today. In Scandinavia, the tradition of Julegrisen—the Marsipan Yule pig—is a beloved part of modern holiday celebrations.

(Julegrisen)

Jacob Grimm, in his 19th-century work on Germanic traditions, also observed a potential survival of this ancient custom in the serving of a boar’s head at Christmas banquets. This tradition, particularly noted at The Queen's College, Oxford, may be a direct descendant of the Yule boar-blót, keeping alive a practice that spans millennia. These connections illustrate how ancient Yule rituals have influenced and evolved into modern holiday customs.

The tradition of swearing oaths on the sacred Yule boar is also recounted in Helgakviða Hjörvarðssonar, one of the Poetic Edda poems believed to date back to the earliest periods of Norse oral tradition. This text describes a nearly identical ritual to the one mentioned in Hervarar Saga ok Heiðreks, where participants place their hands on the sacrificial boar and swear their oaths during Yule.

"Um kveldit [jólaaftan] óru heitstrengingar. Var fram leiddr sónargöltr. Lögðu menn þar á hendr sínar ok strengðu menn þá heit at bragarfulli.

That evening [of Yule Eve] the great vows were taken; the sacred boar was brought in, the men laid their hands thereon, and took their vows at the king's toast."

-Helgakviða Hjörvarðssonar

This account strengthens the case for the historical authenticity of such practices, countering the argument that Viking sagas, written down in the 13th century, are entirely unreliable because they were recorded by Christians. While it is true that Christian scribes preserved many of these texts, Helgakviða Hjörvarðssonar predates the written sagas and can be traced to the 5th century at it's origin, supporting the credibility of these traditions.

Dismissing the sagas as mere fabrications ignores the wealth of corroborative evidence from archaeology and older oral tales. Norse religious practices are not simply speculative or "made up." Many of the sources we have—both written and material—paint a detailed and consistent picture of these rituals. Serious engagement with these records, rather than selective reading or outright dismissal, is essential for reconstructing and understanding the richness of Norse tradition.

Gift Giving and Merry Making During Yule

Gift giving was undoubtedly a part of Yule celebrations, as vividly illustrated in Egil’s Saga (Egils saga Skallagrímssonar). During the festivities, Arinbjörn, a generous host, presented luxurious gifts to Egil and all his guests.

"In the winter Egil went southwards to Sogn to collect his land-rents, staying there some time. After that he came north again to the Firths. Arinbjorn held a great Yule-feast, to which he bade his friends and the neighbouring landowners. There was there much company and good cheer. Arinbjorn gave Egil as a Yule-gift a trailing robe made of silk, and richly broidered with gold, studded with gold buttons in front all down to the hem. Arinbjorn had had the robe made to fit Egil's stature. Arinbjorn gave also to Egil at Yule a complete suit newly made; it was cut of English cloth of many colours. Friendly gifts of many kinds gave Arinbjorn at Yule to those who were his guests, for Arinbjorn was beyond all men open-handed and noble."

-Egils saga Skallagrímssonar ch.70

In response to this act of generosity, Egil composed a heartfelt thank-you poem, showcasing the reciprocal nature of gift-giving and the strong bonds of community fostered during Yule.

"Then Egil composed a stave:

'Warrior gave to poet

Silken robe gold-glistering:

Never shall I find me

Friend of better faith.

Arinbjorn untiring

Earneth well his honours:

For his like the ages

Long may look in vain.'

-Egils saga Skallagrímssonar ch.70"

Another example in the Olav's saga Helga accounts plenty of gift giving at Yule. Without doubt, there is some link to our modern Christmas gift giving during this season of the year.

“In the winter Eyvind was at the Yule feast with King Olav and there he got gifts from him. Brynjulv Ulvaldi was also there with him, and he got as a Yule gift from the king a gold-dight sword and thereto the garth called Vettaland, which is a great manor farm.”

-Óláfs saga helga ch. 62

The Post-Yule Depression: Reflecting on the Days After Celebrating Yule

Interestingly, Egil’s Saga also provides a glimpse into the emotional aftermath of Yule. After the festivities ended, Egil fell into a deep depression as the reality of his troubles for the coming year set in. This post-Yule melancholy is something many of us can relate to, likened to the emotional "comedown" after an intense celebration.

"Egil after Yule-tide was taken with much sadness that he spake not a word. And when Arinbjorn perceived this he began to talk with Egil, and asked what this sadness meant. 'I wish,' said he, 'you would let me know whether you are sick, or anything ails you, that I may find a remedy.'

Egil said: 'Sickness of body I have none; but I have much anxiety about this, how I shall get that property which I won when I slew Ljot the Pale northwards in Mæra. I am told that the king's stewards have taken up all that property, and claimed ownership thereof for the king. Now I would fain have your help in the recovery of this."

-Egils saga Skallagrímssonar ch.71

Perhaps this sense of post-celebration sadness is ingrained in our genetic memory, a lingering echo of the cycle of communal joy followed by the return to the challenges of daily life. Egil’s story reminds us of the emotional highs and lows that often accompany the winter season’s most vibrant and meaningful celebrations.

Supernatural Events During Yule: A Time When the Veil Is Thin

In Grettir’s Saga (Grettis saga Ásmundarsonar), chapters 32 to 35 recount supernatural events that take place around Yule. These events add a darker, mystical dimension to the season, blending the physical and spiritual worlds.

The story centers on a man named Glámr, who was hired by a Christian farmer to guard his livestock. Glámr, likely a pagan, refused to observe Christian Yule traditions, including fasting during the holiday. On Yule night, Glámr disappeared, and his body was found the next morning, apparently after a violent encounter. Following his burial, Glámr’s spirit returned as a draugr (a restless undead being), haunting the area and spreading fear among the locals.

Not long after, Grettir arrived and faced the undead Glámr in a fierce battle. Grettir ultimately prevailed, chopping off Glámr’s head and ending the haunting. This dramatic scene highlights the enduring ties between Yule and the supernatural, with themes of death, spirits, and the thin veil between worlds. Interestingly, this moment from Grettir’s Saga served as inspiration for a scene in the film The Northman, demonstrating the lasting influence of Norse sagas on modern storytelling.

The Yule season in Grettir’s Saga portrays a time when the boundary between the natural and supernatural worlds becomes thin, akin to the traditions of Vetrnætr and its parallels, such as Halloween, Samhain, and Día de los Muertos. Yule, too, was seen as a period ripe for supernatural activity, where spirits and otherworldly forces were believed to be more accessible.

This belief persisted long after the pagan era, surviving in Scandinavian folk traditions. One of the most notable of these is Årsgång (the Yearly Walk), a ritual typically performed at Christmas or New Year. During this practice, individuals would venture out into the night to seek insights from spirits and gain prophetic visions of the coming year.

Such traditions highlight how Yule was not only a time of feasting and community but also a season steeped in spiritual and mystical significance, bridging the human and supernatural realms.

No Violence for 3 Days: Peace Agreements During Yule

In Norse tradition, Yule was not only a time for feasting and celebration but also a period of peace and respite from hostilities. This is notably illustrated in Orkneyinga Saga (The History of the Earls of Orkney), which mentions Yule around 50 times, mostly as a marker of midwinter and a time for great feasting. However, it also emphasizes the idea that no fighting should occur during the three days of Yule. Despite conflicts often erupting around Yule, there was a strong cultural preference to avoid violence during the festival, and in some cases, efforts were even made to broker peace during this sacred time as you can see from the various quotes below.

Quotes from various points in the saga:

-At Yuletide King Harald came to Biörgvin, and lay in Flóruvagár till after Yule. Then they attacked the town, and met with little resistance.

-They did as Erling advised, and when they had finished their work Yule was close at hand. The Bishop would not 138permit the inhabitants of the castle to be attacked during the Yule-tide.

-The tenth day of Yule-tide was a fine day, and Earl Rögnvald arose and commanded his men to arm themselves, and summoned them with trumpets to the attack of the castle. They dragged the wood close to it, and heaped up large piles round the walls. Then the Earl gave orders where each should make the attack.

-A conference took place between the Earls at Kirkiuvag (Kirkwall), and at that conference they confirmed their peace with oaths. It was two nights before Yule when they made peace, and the terms were, that they should each have one-half of the Islands, and both should defend them against Earl Harald or any other if he claimed them.

-Swein went to Thingavöll,[427] to his father’s brother Helgi; and there they spent the first days of Yule in hiding. Earl Rögnvald went to Daminsey, but Earl Harald was at Kirkiuvag during Yule-tide. Earl Rögnvald sent men to Thingavöll, to Helgi, and asked him to tell his kinsman Swein, if he knew anything of his whereabouts, that Earl Rögnvald invited him to spend the Yule with him, and he would try to make peace between him and Earl Harald. When Swein received this message, he went to Earl Rögnvald, and remained with him during the rest of the Yule-tide, and was well treated.

-After Yule-tide the King sent word to all the chiefs in his kingdom, and collected a large army throughout the country, and with all these troops he went down to Caithness against Earl Harald.-Orkneyinga Saga

This principle is echoed in Halfdan the Black’s Saga, though with a darker twist. In this story, King Halfdan the Black captured a Finnish wizard who had stolen all the food from a Yule feast. While the wizard was tortured for his actions, Halfdan refrained from killing him, adhering to the Yule prohibition against violence. Interestingly, it was Halfdan’s son, Harald Fairhair, who felt his father was cruel to do this at such a holy time, he later helped the wizard escape. In retaliation, the wizard used magic to orchestrate Halfdan’s death by having him fall through the ice, paving the way for Harald Fairhair to become king as a young boy. This tale underscores how seriously the no-killing rule during Yule was taken, even in situations involving betrayal and theft.

"King Halfdan was at a Yule-feast in Hadeland, where a wonderful thing happened one Yule evening. When the great number of guests assembled were going to sit down to table, all the meat and all the ale disappeared from the table. The king sat alone very confused in mind; all the others set off, each to his home, in consternation. That the king might come to some certainty about what had occasioned this event, he ordered a Fin to be seized who was particularly knowing, and tried to force him to disclose the truth; but however much he tortured the man, he got nothing out of him. The Fin sought help particularly from Harald, the king's son, and Harald begged for mercy for him, but in vain. Then Harald let him escape."

-Halfdan the Black's saga

In another example, The Saga of Magnus the Blind recounts that no work was permitted during the three days of Yule, further reinforcing the idea of Yule as a time for rest, reflection, and community harmony. These accounts highlight the sacred nature of Yule as a period of peace, where violence and even labor were seen as inappropriate, reflecting the deep cultural and spiritual reverence for this midwinter festival.

“On the eve of Yule (jólaaftan) King Harald came to Björgyn and brought his ships into Floruvagar. He would not fight during Yule because of its holiness. But King Magnus got ready for him in the town. He had a sling raised out on Holm and he had chains made of iron and partly of tree stocks; he had these laid across the Vag from the king’s residence. He had foot-traps forged and cast over Jonsvolds, and Yule was kept holy for only three days, when no work was done.”

-Saga of Magnús blindi

Drinking at Yule: Rituals and Feasting During the Yuletide Winter Solstice

One final aspect of Yule, so commonly mentioned in Norse sources that specific quotes are unnecessary, is the presence of alcohol. Mead, ale, beer, or any other available alcoholic beverage played a central role in Yule celebrations. There is no debate—Yule was a time for feasting and drinking, often to excess. Dozens, if not hundreds, of references to alcohol during the Viking Age can be found throughout the Norse sagas, especially in connection with winter festivities and Yule itself. Simply read any Norse saga, and within a few chapters, you are likely to encounter examples of drinking during this time of year.

Alcohol also held a sacred place in Norse paganism, woven into mythology, ritual, and other sacred rites. It was more than just a celebratory drink—it was an integral part of spiritual practices. For more insights into the role of alcohol in the Norse religion, check out our blog post and accompanying YouTube video.

So yes, Yule was historically a time to indulge in alcohol as part of the celebration and religious observance. However, if alcohol does not sit well with you or aligns poorly with your personal values, it may be challenging to fully embrace Norse paganism as it was historically practiced. Understanding and respecting the historical roots of these traditions is essential for those wishing to follow the old ways authentically.

Yule Conclusion: Exploring the Roots of Christmas and Yule Traditions

As we have explored, there are numerous parallels between the Norse and Germanic traditions of Yule and the modern-day celebrations of Christmas. From feasting, gift-giving, and oaths to themes of peace and supernatural occurrences, many aspects of Yule have clearly influenced the holiday festivities we know today. However, some elements—such as the Christmas tree, wreaths, or figures like Santa and his reindeer—are not explicitly mentioned in Norse sources.

That said, when we delve into the symbolism of Norse myths, later folk traditions with probable pagan origins, and solstice practices from neighboring cultures such as the Sami, we can piece together a fuller picture of the deep-rooted connections between these ancient customs and modern celebrations. These symbolic and cultural threads provide a fascinating lens through which to view the traditions we hold dear today—but that is a topic for another time.