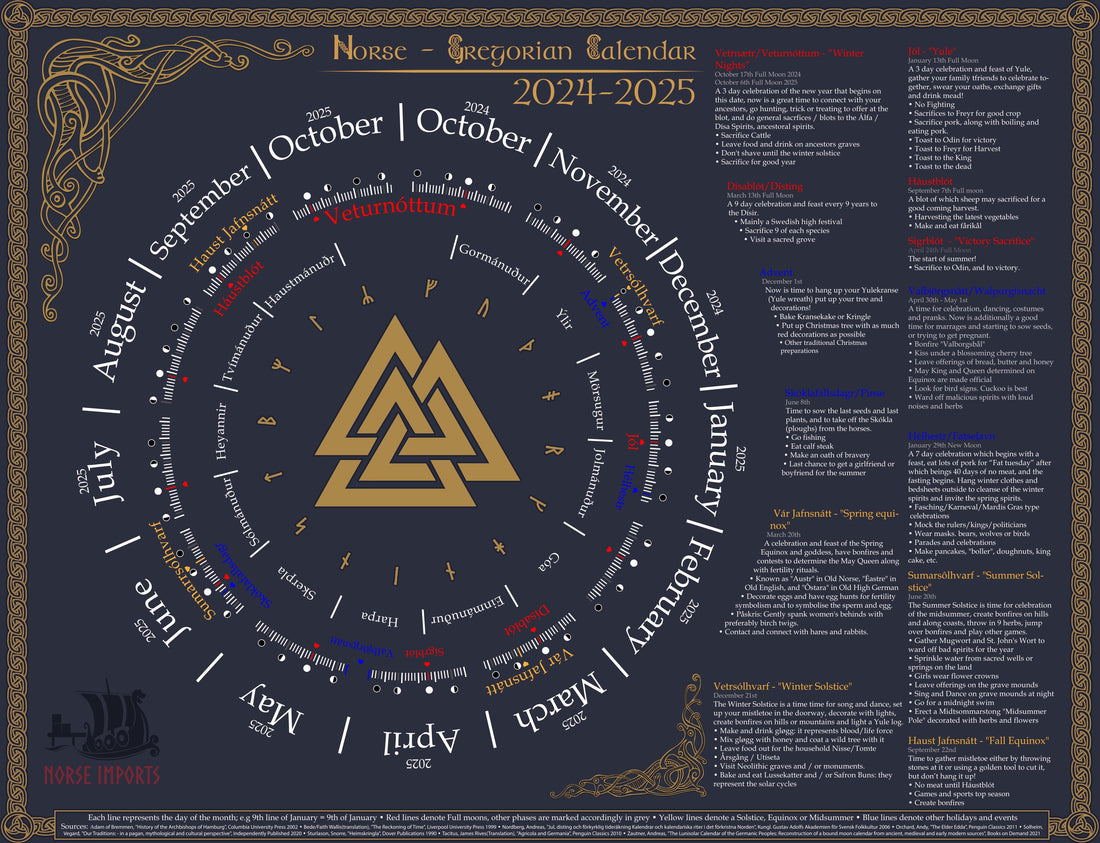

Norse Calendar & Pagan Holidays Wheel of the Year Explained with Sources

Share

Intro

This text serves as a guide on how to read and use our Norse calendar for sale here

Our Calendar

https://norseimports.com/collections/norse-calendars-viking-flags

vs

The Wicca Wheel of the Year

As opposed to the traditional Wicca wheel of the Year which was created in the last century incorporating both Norse and Celtic pagan holidays(often on the complete wrong date), our calendar is based on the written sources dating back 600-2000 years. This calendar features all the holidays, dates, celebrations, and even a guide on how we can practice these ancient traditions today. A calendar like this has never existed before, and for good reason. I, along with many others, have wanted to create such a calendar for years, but the research and organization required for this monumental task, along with finding a designer willing to take on such a project, seemed impossible.

However, a very creative designer perfect for the job named Lucas O'Neil was able to bring this calendar to life!

Although this calendar is beautifully designed and made to be easy to read and follow along with the dates, some aspects require explanation, which is what this article is for. This Norse calendar, like any other, is reconstructed. We don’t know exactly what kind of calendar they used in pagan times—or if they even had a standardized one at all. Different historians may reconstruct these calendars slightly differently, but the key is that the calendar should be based on the sources we do have. Every detail on our calendar is directly linked to historical sources or can be explained using those sources. At the bottom of the calendar, we’ve included all the sources we used, so you can read them yourself if you’re interested. Now, let's dive into the explanations!

Moons & Months

First, notice the months of our Gregorian calendar in parallel with the Norse lunar system with months listed on the inner layer of the wheel. The Norse, like many other ancient cultures, followed the phases of the moon—this is actually where the word "month" comes (Old Norse: mánuður “moon.”)

There is some scholarly debate about whether Norse months began with the new moon or the full moon. We decided to align the start of the month with the full moon. One reason for this is that the Germanic tribes believed the new day began at sunset, as recorded by Tacitus, Germania in the 1st century. So it stands to reason that their new month might also begin when the moon was at the start of the waning cycle.

Additionally, historical evidence suggests that sacrifices, or blóts, often took place during the full moon, and it was also likely when the new year and winter season began. For example, Bede’s Reckoning of Time accounting the pagan Anglo-Saxons in the 8th century and other Norse sources support the idea that the full moon was an important marker for holy days in their calendar.

Keep in mind, the Anglo-Saxons and the Norse shared the same pagan traditions if we go far enough back in time. For these reasons, we chose the full moon to signify the start of each new month and the time for the major sacrifices and festivals of the year.

For the month names, we used the traditional Icelandic calendar, which many of you may be familiar with. This system is based on month names being attested as early as the 12th century, though some aspects are a bit conflicting with other more recent sources.

Old Icelandic Month names

Gormánuður: The first month of winter, which is also known as "slaughter month".Ýlir: The second month of winter, which is also known as the "Yule Party Month".

Mörsugur: The third month of winter.

Þorri: The fourth month of winter, which is well known for the Þorrablót festivities.

Góa: The fifth month of winter.

Einmánuður: The last month of winter.

Harpa: The first month of the summer, and the first month of spring. The name means "harp".

Skerpla: The second month of summer.

Sólmánuður: The third month of summer, which translates to "sun month".

Sumarauki: A short period of 4–11 days added between the third and fourth summer months to correct the calendar.

Heyannir: The fourth month of summer, which means "haymaking".

Tvímánuður: The fifth month of summer, which means "two months".

Haustmánuður: The last month of summer, which means "autumn month".

We made two key changes for the months of our calendar. First, we renamed the month Þorri to Jólmánuður, meaning "the moon of Yule" which would be around this time. Bede also refers to this month as Gēola, which is the Old Anglo-Saxon cognate of Jól.

The second alteration, in some years we add a 13th month to account for the way lunar calendars gradually fall behind solar cycles due to their shorter length. Every three to four years, people would observe the lunar and solar cycles and decide if an additional month was needed, as described by Bede. The Primstav (Norwegian calendar stick) dating back to the 14th century also reflects this practice.

One Archeological Find of the Primstav

Though we don’t know what this month was called in the Norse tradition, the Romans referred to it as Mercedonius, meaning "work month." So, we translated that into Old Norse and named it Yrkjamánuður "Work Month." This month is added every 3-4 years.

Lastly, we have mapped the waxing and waning of the moons on this calendar. This detail is important, as most rituals and practices ware traditionally performed during the waxing moon, not the waning moon. From personal experience and reports from many others in our community, when performing sacrifice, it is curtial to do so not after the moon has begun to wane. If performing a sacrifice on the full moon, it is better to do it a few days too early rather than just an hour too late. Scandinavian folk traditions also record this practice and belief, and it can also be seen in the Eggja Runestone from the Viking age. So, definitely pay attention to the moon phases when planning rituals. Also, be sure to check the local time in your area, as the full moon will occur at different times depending on your location.

The Eggja Runestone inscription

-"No man may lay it bare, when the waning moon runs. Misguided men may not lay [the stone] aside. "

Vetrnætr/Veturnóttum ("Winter Nights")

Let’s dive into the holidays, starting with the Norse New Year, which kicks off with Vetrnætr (Winter Nights), also known as Veturnóttum.

Date: The full moon in October

Significance: Marks the start of the Norse New Year

Duration: A 3-day celebration and feast

This is one of the most well-attested festivals in the Norse sagas. Multiple sources mention it, including the sagas in Heimskringla and many of the Sagas of the Icelanders dating to the 13th century but accounting much older events.

This is the main source that documents the Norse New Year to be at the start of the winter along with another Anglo-Saxon source telling of a similar celebration called Winterfylleth, according to Bede in the 8th century when England was still pagan. Here's a breakdown of what happens during Vetrnætr:

Sacrifices for a Good Year: According to Heimskringla, Ynglinga Saga, this festival involved sacrifices for a prosperous year ahead. These sacrifices often included cattle, as they were critical for survival through the harsh winter months.

Álfablót/Dísablót (Honoring the Elves, Female, and Ancestral Spirits): Some sagas tell about a sacrifice to the elves and disir(male & female ancestral spirits-see The Tale of Olav Geirstadalv). Though these specific sacrifices could also be observed at other times throughout the year according to other sources, in general it is logical to place them in our month of October as this is a time for honoring ancestral spirits in many cultures(compare Dia de los Muertos). The veil between our realm and the next is the thinnest at this time of year and is naturally the best time to connect to our ancestors here.

Ancestor Offerings: It was customary to leave food and drink on the graves of ancestors to honor and connect with them. When Christianity came to Scandinavia in the viking age and traditional blood sacrifices became illegal, the people continued to leave offerings of honey, butter, bread and other treats on their ancestors graves even if it was in a Christian graveyard. These ancestral traditions persisted in Scandinavian folk practices until as recently as 1-200 years ago.

Utíseta: This is also a great time of year to practice Utiseta("sitting out). This was a form of meditation or ritual sitting out during the night at a crossroads, or on a burial mound to commune with ancestral spirits. Although this can be done at any time of year, it would of course be most effective in our month of October when the veil is thinnest between our world and the next.

Trick or Treating: A form of early "trick-or-treating" involved children visiting neighboring farms to gather gifts and offerings for the blót. Children were encouraged to dress as ancestral spirits or wearing bird or winged costumes was also common. This is recorded in the more recent folk tradition(see Våre tradisjoner by Vegard Solheim)

The Wild Hunt: While often associated with Christmas or the later New Year, some evidence suggests the Wild Hunt was originally part of this pagan New Year celebration. Even to this day, the late fall-early winter if the prime time for hunting and in older times we find tales of spectral huntsmen roaming the skies and other world in our folklore.

No Shaving Until Winter Solstice: The modern "No Shave November" or "Movember" tradition may have ancient roots in sympathetic magic. In connection with the myth of Odin's son Váli, Norsemen may have let their hair and beards grow until the Winter Solstice, representing the cycle of death and rebirth. When everything in nature stopped growing and this was often the time to plant the earliest seeds and let them germinate over the winter, humans mirrored this by letting their hair grow until the sun "returned" at the Solstice—symbolic of Baldr's eventual return. We discuss this tradition in another blog post that we will link here.

This makes Vetrnætr a rich, multifaceted celebration with deep roots in Norse tradition, from honoring ancestors to preparing for the long winter ahead.

Advent

Date: November 27th or December 1st

Advent is a well-loved tradition in Norway and many other places, and while it is commonly associated with Christianity, it has much deeper roots in pagan customs. If there’s one thing to remember here, it’s that the vast majority—around 90% or more—of what we now consider Christian holidays were originally pagan. There are dozens of primary sources from not just Scandinavia, but all over the North of Europe confirming how Christian rulers simply altered the dates and names of pagan holidays to help with conversion. But it does not take a genius to see that traditions themselves did not come from the desert with Christianity. Many of these clearly show much older native European roots.

Many of the following traditions are not recorded in sources accounting for pagan times, but they are recorded in the more recent folk tradition. See "Våre tradisjoner" for more details.

Traditional Practices:

Hang up Julekranse (Christmas Wreaths): This practice has pagan origins and is linked to the cyclical nature of the seasons and the returning sun.

Bake Kransekake or Kringle (Circular Pastries): These circular pastries symbolize the returning solar cycles, marking the rebirth of the sun during the darkest days of winter.

Put Up the Christmas Tree: The Christmas tree is also a deeply rooted pagan tradition. Red decorations are particularly significant, symbolizing blood and the life force. This is a tradition recorded more often in the Sami regions of Scandinavia.

This time is all about circular cycles and the return of the sun/light. There are many more customs surrounding advent with this cycle in mind. As you prepare for the holidays, just celebrate as you normally would—keeping in mind that these traditions are part of an ancient heritage. You can be the judge of which ones are pagan vs Christian in origin!

Vetrsólhvarf ("Winter Solstice")

Date: This year, December 21st

It's important to clarify that this is NOT Jól/Yule. Many modern pagans have incorrectly placed Yule on the Winter Solstice, likely influenced by the Wiccan Wheel of the Year. However, this was never the original Norse Jól. In Viking times, it was celebrated on the first full moon after the Winter Solstice. It was only later in the late 900s, during the reign of the Christian Viking king, Haakon the Good, that Jól was moved to align with Jesus’ birthday in December in an effort to Christianize the Norwegians. But traditionally, Jól was in January.

Winter Solstice Traditions (From the later Scandinavian/Sami Folk Tradition):

Hang Mistletoe in the Doorway: Don't hang the mistletoe before the Solstice. It was traditionally collected at the equinox(as the Celts also practiced), but it shouldn’t be hung until the Winter Solstice. This will be explained in more depth in the Autumn Equinox section.

Decorate with Lights: Symbolizing the returning light.

Song and Dance: Commonly performed to celebrate the rebirth of the sun.

Bake and Eat Lussekatter (Saffron Buns): These buns represent the solar cycles and are traditionally eaten during the solstice.

Make and Drink Gløgg (Mulled Wine): This drink represents blood and life force. You can also mix gløgg with honey and coat a wild tree with it as part of the solstice celebrations.

Light the Yule Log in the Fireplace: It can be carved with runes for added symbolism. The Yule log represents the light and warmth needed to carry the community through the darkest days of winter.

Light Bonfires on Hills or Mountaintops: This was recorded by Greek explorers Pytheas and Procopios and is a popular tradition that represents the return of the sun’s light.

Leave Food Out for the Household Nisse/Tomte: This Swedish tradition honors the house spirits.

Årsgång (The Yearly walk): A traditional practice of walking at midnight to gain spiritual insight and prophecy for the coming year. See Trolldom by Johannes Gårdbäck

Visit Neolithic Graves/Monuments: If you are lucky enough to live near one of these ancient sites, many of them are aligned with the winter solstice sunlight. Visiting these sites on the solstice connects you to the ancient reverence of the solar cycle.

The Winter Solstice is a powerful time of rebirth and renewal, celebrated through light, food, and connection with the earth and spirits. While the Norse-specific practices around the solstice aren't fully recorded, we can infer much from folk traditions and the universal importance of the sun's return.

Jól ("Yule")

Date: Full Moon(after the NEW MOON) after the Winter Solstice

"Odin established the same law in his land that had been in force in Asaland.[...] On winter day there should be blood-sacrifice for a good year, and in the middle of winter(Jól) for a good crop.

-Ynglinga Saga

There are many historical sources accounting the viking age that mention Jól celebrated by pagans, including Ynglinga Saga, Halfdan the Black’s Saga, Harald Fairhair’s Saga, and Haakon the Good’s Saga. I will link another blog article here for an in depth explanation here. Below are some of the key festivities summarized

3-Day Celebration and Feast: The celebration of Jól traditionally lasted for three days, with feasting being a central part of the event.

No Fighting: During Jól, it was forbidden to engage in fighting, emphasizing the holiday’s role as a time of peace and togetherness.

Sacrifices (Blóts): To Freyr, for a Good Crop: Freyr, the god of fertility and harvests, was honored with sacrifices to ensure good crops for the coming year.

Sacrifice Pork/Boar: As Freyr’s sacred animal, the boar was often sacrificed during Jól.

Boil and Eat Pork: A traditional part of the Jól feast. We have included a recipe for boiled pork in the latest years calendar with all ingredients that would have been available to the Norse at the time.

Drink Mead: Mead was an essential part of Viking celebrations, especially at Jól.

Toasts: Specific toasts were made during the Jól feast: A toast to Odin, for victory in battles. A toast to Freyr, for a bountiful harvest. A toast to the King and a toast to the Dead, honoring the ancestors.

Swearing Oaths: Jól was also a time for swearing oaths, which were considered binding and sacred.

Gift Giving: Exchanging gifts was a key part of the celebration, symbolizing generosity and kinship.

These traditions, steeped in history and mentioned in various sagas, form the backbone of the Jól celebrations, showcasing the importance of community, peace, and prosperity during this sacred time of year.

Hélhestr/Fastelavn

Date: New Moon in February

This holiday is explained in great depth in Våre tradisjoner by Vegard Solheim that you can read more about here. This is another that there are no direct mentions of from the viking age sources. But there are plenty of records coming from the folk tradition. This celebration mirrors other festivals around the world at the same time, like Fasching, Karneval, and Mardi Gras, which all take place between late February and March. Though these festivals are often considered Christian traditions, there is plenty of evidence that they originated from earlier pagan customs, especially when we look at similar celebrations in Germany.

Hélhestr/Fastelavn Festivities:

7-Day Celebration: This was likely the biggest and longest festival of the year, filled with feasting and revelry.

"Narrenruf" (Local Greetings): Each town in the German speaking regions of Europe and even elsewhere in the world has its own traditional party greeting, so check to see if your area has one!

40-Day Fast: Contrary to popular belief, fasting and abstaining from meat for 40 days is not solely a Christian practice. It was common among ancient rural societies. This fasting period, which makes practical sense during this time of year, is also discussed in another blog article here.

Mocking Rulers and Kings: This time of year traditionally involved making fun of leaders and authority figures. It’s the perfect time to roast politicians you don’t like today!

Wearing Masks: Traditional masks include representations of bears, wolves, or birds. Carneval celebrations in Brazil do a great job keeping this tradition alive.

Parades: A vibrant and essential part of the festivities.

Feasting on Pork: Known as "Fat Tuesday" in modern traditions, this day was marked by indulgence before the fasting period began.

Pancakes, "Boller," Doughnuts, and King Cake: Eating rich and fatty foods is part of the tradition as people prepared to enter the fasting period.

Cleansing Winter Spirits: A final custom is to hang winter clothes and bedsheets outside, symbolically cleansing them of the winter spirits and welcoming the warming sun. This is a way of embracing the end of the cold season and making way for the new growth and warmth that spring brings.

Hélhestr/Fastelavn was a time of celebration, feasting, and community, closely tied to the rhythms of the season and the transitions of the natural world. Many of these ancient customs are still alive today, even if they’ve evolved under different names or in different forms.

Dísablót

Date: March Full Moon

Dísablót is one of the more challenging festivals to pinpoint with certainty. Scholar Andreas Nordberg places it on the third full moon after the Winter Solstice, which this year falls in early March. While we are not 100% certain there was a sacrifice during this time, it strongly appears so from the accounts of Adam of Bremen, who describes sacrificial practices in Viking Age Sweden in the late 11th century.

"It is customary also to solemnize in Uppsala, at nine-year intervals, a general feast of all the provinces of Sweden. From attendance at this festival no one is exempted Kings and people all and singly send their gifts to Uppsala and, what is more distressing than any kind of punishment, those who have already adopted Christianity redeem themselves through these ceremonies. The sacrifice is of this nature: of every living thing that is male, they offer nine heads with the blood of which it is customary to placate gods of this sort. The bodies they hang in the sacred grove that adjoins the temple."

-Adam of Bremmen, Gesta Hammaburgensis 11th century

Dísablót Festivities:

Sacrifice to the Dísir: These are female spirits, often linked to ancestors or protective deities. The specific rituals are unclear, but it is believed the sacrifice was made to honor or appease the Dísir.

Sacrifices: While it’s not certain, Adam of Bremen’s account suggests there may have been a large-scale sacrifice during this time, especially in Sweden. There are records of sacrificing 9 of each species, which was said to take place every nine years.

9-Day Celebration (Every 9 Years): According to both Adam of Bremen and Thietmar of Merseburg, this high festival included a 9-day celebration every 9 years, possibly tied to these larger sacrifices.

Feast: As with most Viking festivals, feasting was an integral part of the celebration.

Sacred Groves: If you have access to a sacred grove, it’s traditional to visit one during Dísablót. The ancient pagan temple at Uppsala had a famous sacred grove where rituals like these may have taken place.

That’s about all we know regarding Dísablót. It was primarily a Swedish high festival, and although details are sparse, the event’s connection to sacrifice, female spirits, and sacred sites suggests it was an important time of renewal and honoring the divine feminine forces within the Norse cosmology.

Vár Jafnsnátt ("Spring Equinox")

Date: March 20th(Easter parallel & pagan origin)

While there aren’t any direct Norse sources about the Spring Equinox, this festival is well-documented in Old English and Saxon pagan sources such as Bede's The reckoning of time in the 8th century reflects a much older pagan origin of Easter. The equinox was celebrated across Germanic cultures, and though it doesn’t have specific Norse mentions other than the goddess of the same name(Austr), it’s clear from the later on recorded folk traditions that this time of year was tied to fertility rituals all over the North of Europe.

Ostara (1884) by Johannes Gehrts.

Spring Equinox Festivities:

Feast/Celebrate the Goddess: This time of year was traditionally associated with fertility goddesses, known by different names across Germanic cultures.

Old English: Ēastre

Old High German: Ôstara

Old Norse: There isn’t a direct attestation of Austr in Old Norse mythology, but the connection to a fertility goddess is undeniable. This is the origin of the name "Easter." As we know, the Christian Easter holiday was a repurposed pagan fertility festival, with many of the rituals absorbed and adapted to fit the Christian framework.

Decorate Eggs: Eggs, a symbol of fertilization and rebirth, were traditionally decorated. This practice has clear pagan roots and is an important symbol of spring.

Egg Hunt: Just like sperm hunts for the egg in fertilization, the Easter egg hunt that we do today symbolizes the fertility cycle.

Påskris: A Swedish folk tradition where women are gently spanked with twigs (preferably birch), symbolizing fertility and life force. This is also done in many traditional Slavic cultures to this day.

Contact/Connect with Hares: Hares are commonly associated with fertility in pagan traditions, and the connection to this animal further highlights the festival's focus on new life and growth.

Games and Competitions: In many ancient traditions, games and competitions were held during this time to decide who would become the May Queen, further emphasizing the fertility aspect of the celebration.

In essence, the Spring Equinox is a celebration of rebirth, fertility, and the awakening of the earth after winter, with its roots deeply entrenched in pre-Christian, pagan practices.

Sigrblót ("Victory Sacrifice")

Date: April Full Moon

Sigrblót marks the start of summer in the Norse calendar, which, remember, only had two seasons—winter and summer as attested in Ynglinga Saga. This ritual was a significant moment in the transition between seasons, and while we don’t have extensive details about it, the celebration is mentioned in two important Norse sources: Ynglinga Saga and Olav Tryggvasson’s Saga.

"Odin established the same law in his land that had been in force in Asaland.[.....] On winter day there should be blood-sacrifice for a good year, and in the middle of winter for a good crop; and the third sacrifice should be on summer day, for victory in battle."

-Ynglinga Saga

Sigrblót Festivities:

Start of Summer: As noted, the Norse calendar divided the year into two seasons, and Sigrblót signifies the official beginning of the summer season.

Sacrifice to Victory: The central purpose of this ritual was to ensure success and victory, particularly for the coming farming season or for warriors preparing for battle.

Sacrifice to Odin: Since Odin is the god of war and victory, it’s highly likely that Sigrblót involved sacrifices made to him in order to invoke his favor for success, whether in battle or in achieving goals for the coming season.

Although we don’t have many details, Sigrblót is clearly tied to themes of success and victory, with Odin playing a central role. This would have been an important time for making sacrifices to ensure that summer brought triumph, whether in warfare, harvests, or personal endeavors.

Walpurgisnacht/Valbjörgsnâtt

Date: April 30th - May 1st

Walpurgisnacht, or Valbjörgsnâtt, is yet another pagan celebration that was rebranded in Christian times, this one named after Saint Walpurga. The festival, however, retains its roots in ancient traditions, with all signs pointing to it as a time to ward off evil spirits and prepare for the coming summer season. While it’s celebrated in various places, Germany is known for having the most vibrant traditions today, though similar customs are preserved in Scandinavia.

Walpurgisnacht/Valbjörgsnâtt Festivities:

Maypole: A central part of the celebration involves decorating a maypole with birch branches and leaves, symbolizing growth and fertility.

Singing, Dancing, Costumes, and Pranks: These lively activities help welcome the new season and drive away lingering winter spirits.

Bonfire ("Valborgsbål"): Lighting a large bonfire is a key tradition, meant to protect the community from evil spirits and misfortune.

Ward Off Evil Spirits: Loud noises, music, and the burning of herbs were commonly used to keep evil spirits at bay during this time.

Kiss Under a Blossoming Cherry Tree: A traditional custom symbolizing love and fertility.

Leave Offerings: Bread, butter, and honey are commonly left as offerings to trees or grave mounds, continuing the theme of honoring ancestors and nature.

May King and Queen: The King and Queen chosen during the Equinox games are officially recognized on this day. This was also a traditional time for marriages, making it an ideal date for engaged couples looking to tie the knot.

Sowing and Fertility: This is an excellent time to begin planting seeds and even trying to conceive, as sympathetic magic encourages these activities to align with the fertile energies of the season.

Bird Signs (Cuckoo is Best): The direction from which a bird, especially a cuckoo, calls is said to be highly significant. Here's what the direction of the call symbolizes in the Scandinavian folk tradition:

North: A sign that good things are coming your way.

South: A positive omen for the harvest, even if dry weather occurs.

West: A warning of sickness or death.

East: A sign of happiness and upcoming marriage.

While most well-known in Germany, many of these traditions are preserved in Scandinavian folk customs as well. Walpurgisnacht is a time to embrace the energies of spring, prepare for the growing season, and connect with nature's fertility through both practical and magical acts.

Skóklafallsdagr/Pinse

Date: June 8th

As Vegard Solheim calls Skóklafallsdagr(read more here), also known as Pinse, is another celebration in Scandinavia that is often considered Christian but has deep pagan roots. Skóklafallsdagr translates to the "Day the Plough is Taken Off," symbolizing the end of the planting and sowing season.

Skóklafallsdagr/Pinse Festivities:

Remove the Ploughs (Skókla): On this day, the ploughs are taken off the horses, marking the official end of planting and sowing for the season. All farming preparation should be finished by now.

Go Fishing: The primstav (traditional Norwegian calendar stick) often features a fish symbol on this day, suggesting that fishing was an important part of the celebration.

Oath of Bravery: This day was also about making a commitment to bravery. People would swear an oath to take on something courageous during the summer, whether it be a physical challenge, a new pursuit, or something meaningful.

Find a Partner: In Finnish tradition, Pinse was the last opportunity to find a girlfriend or boyfriend before the summer. This was a time for socializing and making connections as the warmer season approached.

In short, Skóklafallsdagr/Pinse is a day of transition—finishing the farming season, celebrating the start of summer, and making personal commitments to bravery and growth. Whether through feasting, fishing, or socializing, this day honors both nature and the community's readiness for the active season ahead.

Sumarsôlhvarf ("Summer Solstice")

Date: June 23rd

Though we don’t have any specific Norse records of the solstices being celebrated, it's highly likely that the Summer Solstice, like the Winter Solstice, was observed in some form. Nearly all ancient cultures celebrated the solar cycles, and we have several folk traditions from Scandinavia that are still celebrated today, which reflect those ancient practices.

Summer Solstice Festivities:

Bonfire: A large bonfire is central to the celebration. Traditionally, people would throw 9 herbs into the fire, symbolizing protection and abundance for the coming year.

Jump Over the Fire (Safely): Games such as jumping over the bonfire were commonly played, symbolizing vitality and the energy of the season.

Multiple Small Bonfires: Small fires along hills and coasts are often lit, sometimes believed to represent Brísingamen, the necklace of the goddess Freya.

Midsummer Pole (Midtsommarstong): In Sweden and other parts of Scandinavia, the Midsummer Pole is decorated with herbs and flowers, symbolizing fertility and the peak of growth in nature.

Gather Mugwort and St. John's Wort: These herbs, known for warding off bad spirits, are traditionally foraged at this time of year. Once dried, they are kept around the house for protection throughout the year.

Sprinkle Water from Sacred Wells: Water from sacred wells or springs is collected and sprinkled on the land as a blessing for prosperity and good fortune.

Girls Wear Flower Crowns: Flower crowns made from seasonal blooms are worn, a long-standing tradition that connects the wearer with nature and the fertility of the earth.

Offerings on Grave Mounds: Offerings are often left on the grave mounds of ancestors, continuing the practice of honoring those who came before.

Sing and Dance on Grave Mounds: If there are grave mounds nearby, singing and dancing upon them at night is a way to celebrate life and connect with ancestral spirits.

Midnight Swim (Skinny Dip): In many parts of Scandinavia, it’s a tradition to take a midnight swim, often done in the nude, symbolizing a connection with nature and the cleansing power of water.

Sumarsôlhvarf is a time to celebrate the height of summer and the abundance of the natural world. Through bonfires, herb gathering, dancing, and offerings, it reflects the interconnectedness of people with the land, the sun, and the spirits. While the ancient Norse might not have left us detailed records of how they celebrated, these Scandinavian folk traditions offer a glimpse into the ancient customs and reverence for the power of the sun.

Period of Summer Work

After the solstice, we enter a period of a couple of months without major holidays. Some years, it's even longer due to the additional month added, Yrkjamaanudur (Work Month). There's a good reason for this gap in festivities—ancient humans were incredibly busy during this time, working hard on farms or going on rids or trading missions from July until the harvest. These 2-3 months were filled with long days of labor, ensuring a successful crop for the rest of the year.

Now is the perfect time to focus on your own projects and goals. If there’s anything you want to accomplish, this is when to power through. It's in our DNA to work hardest during this part of the year, tapping into that ancient rhythm of productivity.

One holiday during this time comes from the Celtic world in early August called Lammas, which may have a Norse equivalent. However, I didn’t include it in this year’s calendar—perhaps next year.

Haust Jafnsnátt ("Fall Equinox")

Date: September 22nd

The Fall Equinox marks a significant turning point in the year, where the balance of light and dark shifts, and we begin to prepare for the colder months ahead. Although there are fewer written Norse sources on this event, many traditions have been preserved, some of which are closely tied to ancient rituals.

Haust Jafnsnátt Traditions:

Gathering Mistletoe: The most important tradition around this time is the gathering of mistletoe. In Swedish tradition, mistletoe is gathered by throwing stones at it to knock it down, while in the old Celtic druid tradition, mistletoe is cut down using a gold tool. This practice ties into the myth of Baldr and his eventual resurrection, but don’t hang it up just yet—there’s a time for that later. See the section on the Winter Solstice for that evplanation.

No Meat Until Haustblót: According to tradition, meat is avoided until the Haustblót (fall sacrifice), which isn’t far off, but it’s a good practice to follow if you’re observing the seasonal traditions. It is a bit debated and conflicting from some sources when the Haustblot was exactly. Some years it comes just after the equinox and some years it may fall before. The fasting at this time of year never would have lasted more than a week or two and is not a particularly important custom it seems.

Games and Sports: This time of year is the perfect season for games and competitions. It’s no coincidence that many modern sports seasons begin in the fall, as ancient people also used this period—after things slowed down on the farm—as a time for athletic competitions. It’s a great time to engage in some physical activities or organize some friendly games, much like the ancient Greek Olympics, which also took place around this time of year.

Bonfire: As with many seasonal transitions, lighting a bonfire during the Fall Equinox is a tradition to celebrate the balance of the seasons and to prepare for the darker days ahead.

Haust Jafnsnátt is a time to celebrate the harvest, gather mistletoe for future rituals, and enjoy games and sports as the year shifts toward winter. It’s a moment to recognize the balance in nature while also preparing for the busy rituals to come as the season changes.

Háustblót ("Harvest Sacrifice")

Date: September Full Moon

The Háustblót, or Harvest Sacrifice, is a bit tricky to pin down. In Gísla Saga, the Háustblót was actually celebrated during Vetrnætr (Winter Nights) and the full moon that marked the beginning of the new year. However, there are multiple sources suggesting that Vetrnætr sacrifices were for other purposes, such as blessings for health, good luck, or offerings to the elves (Álfablót) and female spirits (Dísablót). Additionally, by the time Vetrnætr arrived in late October, the harvest would have already been completed in most of Scandinavia, making it more logical for a harvest sacrifice to occur earlier, around mid-late September, which is why we placed it here on our calendar.

Háustblót Traditions:

Sacrifice Sheep: This is the time for a sheep sacrifice to ensure a successful harvest and to thank the gods for the bounty of the season.

Harvesting Late Vegetables: The last of the crops, particularly late vegetables, are gathered during this time to prepare for the colder months.

Make and Eat Fårikål: A traditional Norwegian dish of lamb and cabbage, fårikål is a great way to celebrate the season. It’s one of my favorite Norwegian recipes and perfectly fits the harvest vibe.

Also, incorporating the classic Oktoberfest celebrations around this time is a great idea. Oktoberfest technically starts in September, so it aligns well with the festive, communal spirit of the harvest season.

Conclusion

And with that, we come full circle, back to the Vetrnætr and the start of the new year. I hope you enjoyed this full explanation of the Norse calendar and its celebrations. You can get the calendar on our website as a 3x4' banner and there will also be a digital downloadable version available for purchase.

Thanks for following along, and I wish you all a prosperous and celebratory year ahead!